Sanding

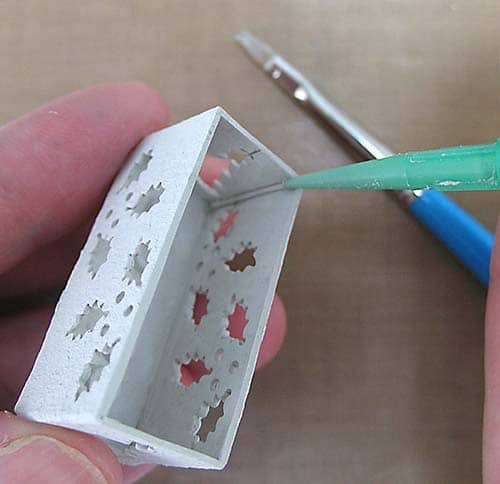

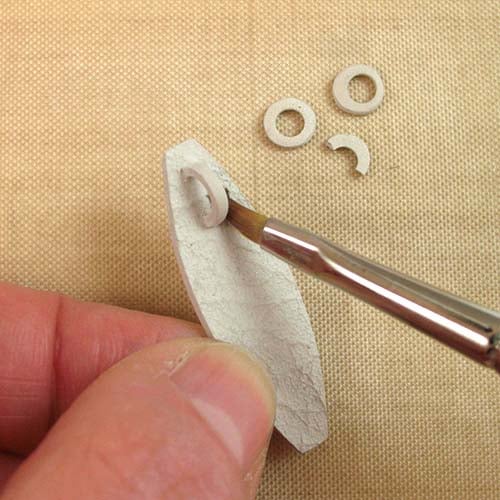

Sanding is a way to refine, alter, and pre-polish work before it is fired. Learning to perfect the edges of a dry piece is usually the first finishing technique students are exposed to, but edges shouldn’t be the only areas taken into consideration. Making sure all aspects of the work are examined before firing, including the back, edges, surface, and any added elements like bails or stone settings, is a necessary part of production. Even the inside of a hole or bail may need some attention.

Dry metal clay is much easier to modify, requires fewer tools, and is less time consuming than working with fired metal.

The assortment of tools and materials that can be used is virtually endless. The most common are:

- Sandpaper from the hardware store

- Salon and emery boards from the beauty supply

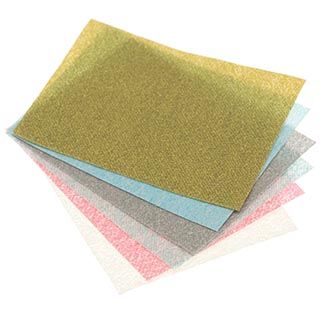

- Jeweler’s finishing/polishing paper

- Sanding sponges

- Small, detail sponges (like eye-shadow applicators)

- Needle files

- Your own fingers

Note: Hardware store sandpaper can be distinguished by color. Grey, wet/dry, papers are generally used for metal and metal clay, and brown paper is more suited for use with wood