The Final Act; or Putting the Right Finish on Your Work

by Linda Kaye-Moses

So… I will talk later about how I approach finishing my pieces, but first I’ll talk about the many traditional processes to find the final surface treatment for your work, many of which I choose not to use. Not because they are wrong processes, but because they are inappropriate or unnecessary for my work.

Most of the tools, equipment, and materials mentioned in this article can be found through major jewelry tool suppliers (listed below), at hardware stores or by searching on the Internet.

What’s this article about?

(OK, so it’s just a Table of Contents)

- What is that fired matte finish and what to do about it?

- Re-moving the surface metal crystals

- After removing the crystals, the flaws come out to play

- What’s the next step; buffing/polishing

- Mass finishing

- The rest of the story; what I like my pieces to look like

- Patination

- My final finishing steps

- Bibliography of some books with the scoop on finishing

- Suppliers

What I won’t be covering

I’m not going to talk about large buffing/polishing machines, because for the most part, these machines are unnecessary (at least in my experience) for metal clay work. However, many of the finishing techniques I will talk about can be transplanted to the large buffing/polishing machines, if you find that type of machine becomes necessary for your work.

Acilius Pied Alongé

What is that fired matte surface and what to do about it?

Let’s assume you’re working with a fully fired and sintered piece. Either it comes out of the kiln with a perfect surface or it’s flawed. Your pieces will always come out of the kiln with a matte look. This is not a flaw. If you like the look of the matte surface, read no further, do not pass go, do not burnish, do not polish.

That matte look of the surface of your piece is the metal crystals that lined-up and stood up during the firing and are a characteristic of sintered metal clay. These crystals can get in the way of seeing any flaws and producing the final finish you may want. Re-moving the crystals will help reveal any flaws, so that’s your first step after taking the piece out of the kiln. You really aren’t removing those crystals; you re-move or compress them by brushing them vigorously.

It was a dark and ugly story

There’s also the very dark surface that can appear on some metal clay pieces. This is different from the crystals noted above. It occurs as a reaction to some of the support materials used in the firing (investment, fiber blankets, etc.). Use your kiln to remove this oxidation surface. Just bury the piece in the carbon even if it wasn’t fired in carbon, program the kiln to hold at 1000˚F (538˚C) for 30 minutes. The piece will come out of the kiln without the dark surface.

Re-moving the metal crystals on the surface of the metal right after firing

Re-moving metal crystals by hand

You have many choices for this process. Here are two:

1. Use a jeweler’s brass brush with a few drops of liquid dishwashing detergent and warm water to brush the surface of the sintered metal. Without the detergent the brass would deposit a yellow color on the surface of your piece.

Why I don’t recommend using steel brushes

Steel brushes are very hard on sintered metal and can really scratch up the surface, scratches you would have to remove later. Brass brushes, on the other hand can burnish your surface, and will impart a very gentle brushed look to the metal, and this look you might want to retain.

2. Use a sheet of Fine Scotchbrite or similar fiber abrasive to scrub the surface of the metal, no lubricant is needed. Scotchbrite is available in sheets in a range of grades, coarse to fine.

Brass brush

Re-moving metal crystals using a rotary tool (flexible shaft or handheld rotary tool)

Scotchbrite, the wonder scrubber again. Cut four 1-inch squares of Scotchbrite. Insert the screw from a screw mandrel through the center of each. Screw the stack of squares onto the mandrel. Insert the mandrel in the rotary tool and run at full speed to scrub the surface of the sintered metal. Scotchbrite wheels can be purchased permanently mounted on a mandrel, but I have found that they wear out too quickly to be economical.

Safety note

For use of all rotary tools, caution must be taken to:

- protect the eyes with safety-rated glasses or a face shield

- protect your lungs, with active ventilation, removing any sanding dust from your breathing space; it’s best to use a good dust collector to remove the particulates created when using a rotary tool.

- protect your hands from damage by a bent or out -of-true

- protect your hair, scalp, and neck by tying back long hair and removing all scarves, ties and jewelry BEFORE sitting down to use a rotary tool.

Flex shaft Rotary tool

Flex shaft safety redux

Every time a mandrel or other tool is inserted in a rotary tool, it should be run slowly and observed from the side to make sure it is running true, that is, there is no apparent bends on or wobble of the shaft of the mandrel.

I run a dust collector and also wear a full face shield EVERY TIME I use my flex shaft! You really do get used to it.

About flex shaft components

The parts of a simple flex shaft machine are:

- a motor

- a shaft in a sheath

- a handpiece with a Jacob’s Chuck or a quick-change handpiece

- a rheostat (foot pedal)

- a stand or other support

- a chuck key

- assorted mandrels

- accessories: sanding, grinding, and polishing wheels; metal and fiber brushes; drill bits; burs; buffs; a small screwdriver

That’s all folks!

And one more note about flex shafts

There are so many accessories available for use with flex shafts it’s impossible for this article to cover all of them.

So, I want to mention the most complete book on these machines, Making the Most of Your Flex Shaft by Karen Christians. This book is a must if you want to know almost everything about these machines. There is a thorough chapter that deals exclusively with the abrasive wheels available for use in rotary tools.

After re-moving the crystals, the flaws come out to play

Checking for Flaws

Now that you’ve re-moved the metal crystals, it’s time to check out the surface for any flaws that will now be more visible. Also, now is a good time to check that any edges that are supposed to be smooth, or parallel, or angles that are supposed to be 90 degrees, are actually what they are supposed to be. Funny things can happen in a kiln when you’re not watching. If your edges are not geometric, but intended to be more organic, check them for roughness, sharpness, or other unwanted irregularities.

To check for accurate parallel edges and 90-degree (right) angles, use a small steel machinist’s or jeweler’s square. This handy tool can be useful before firing, too, for the same purpose. Line up the square at the angle or edge of your piece, and, if the measurements are off, use a permanent marker to mark those spots. If the edges need work, use a flat or half-round file, either hand file or needle file, to refine the flaws you marked.

The Rule for Using a File

Move files toward your piece (away from you), as you work.

After filing, clean up those filed areas with emery paper using grits, progressing from 220 to 600, to remove any file marks.

Dealing with a bumpy or pocked surface

If the surface is bumpy, pocked or flawed in any way, you need to eliminate those flaws before proceeding to final finishing and/or polishing. The type of tool you use will depend on the type of flaw and whether or not you are working with finishing by hand or using a rotary tool.

Needle files

Hand burnishing

Use a polished steel burnisher to compress the marks and bumps. This is easy with sintered metals. Almost any smooth, polished steel object can be used as a burnisher, for example:

- Jeweler’s burnisher

- butter knife

- the back of teaspoon

What are jeweler’s steel burnishers?

Steel burnishers are polished blades, with convex surfaces designed to move and compress metal. The blades are usually around 3-4 inches long and are mounted in a wooden handle. They are available straight or curved. A small amount of light oil can help the tool move more smoothly on the metal. The burnisher is rubbed on the metal surface, following the line of the flaws or pushing on bumps. If the flaws are very small or in a tight space, you can make your own extra-fine burnisher.

How to make your own hand burnisher

Insert the sharp end of a thick (large) sewing needle in a cork. Use 220, 440, then 600 grit emery paper to refine the eye-end of the large steel sewing needle, so that it’s extremely bright and smooth. Rub the needle back and forth on a crocus polishing cloth or on a Sunshine Cloth.

Voila… a burnisher.

If the flaw is even smaller than the above tool will repair, sand the sharp end of the same needle using 220 grit, 400 grit and then 600 grit emery paper. Remove the sharpness but keep a very fine tip on the needle. This time insert the eye end in the cork. Even better than a cork for a handle is a good pin vise that closes down completely. With that tool, you can reverse your needle burnisher as needed.

Some other reasons you might burnish

It’s also necessary to burnish the surface of your metal if you will be soldering any elements to it. This will present a compressed surface to the solder, preventing the solder from sinking into and through the sintered metal surface.

If later on you want to patinate your metal (see below), your results will be much better if the metal is burnished as the first step in finishing your metal surface. A very bright finish on your metal, through burnishing and then polishing, will reflect light, and will help the patina look really good.

Burnishing can be used to brighten specific sections of the metal surface. Burnishing can fix those inevitable flaws before the final finishing of the metal surface.

Machine burnishing

For machine burnishing, use a rotary tool, either a handheld-type tool, or a flexible shaft machine, and an assortment of small steel tooth-free burnishers, Rio Grande is one source for these. Just run the rotary tool at a very slow speed, moving the burnisher against the flaw, smoothing it.

There are also tools called Margin Rollers that can be used in a flex shaft as burnishers. They must be used with care because their action is quite aggressive and easily can create dips or divots in the metal piece.

There are also tools that can be used in a hammer handpiece with a flex shaft. These are used ordinarily for engraving, but include points that are rounded, flat or sharp and can be used to burnish your piece.

Margin Roller

PLEASE SEE FLEX SHAFT SAFETY INFORMATION BELOW

Why I don’t recommend (or use) a hand-held, Dremel-type rotary tool

I don’t find them as convenient in the studio, as easy to hold, or as durable as flexible shaft machines. They are great for portability though, like bringing to a workshop where there are no flex shafts. Otherwise, I prefer the added control and flexibility I get from flex shafts.

Sanding scratches

After the major flaws have been handled, some sneaky scratches may appear on the metal surface.

Sanding unwanted scratches by hand

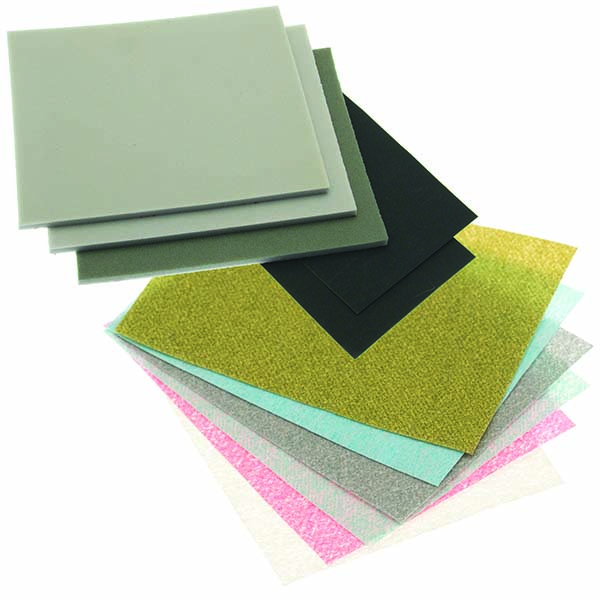

Begin with 220 grit emery paper, continue with 400 grit, then 600 grit, turning your piece 90 degrees with each successively finer paper (i.e., Sand across previous sanding). Progress to finer and finer polishing pads or papers, like Micro-Mesh or Tri-M-Ite or similar products. Check your piece before progressing to the next finest grit. If you still see scratches, go back to the previous coarser grit, then sand, and proceed as above.

Sanding a deeply textured surface is trickier than sanding a smooth surface, but can be accomplished by wrapping the end of a fine-tipped burnishing or dapping tool in polishing papers like Tri-M-Ite, and using that material to get into the textures.

Sanding sticks are useful for applying a little more pressure on emery paper to sand the surface of your metal, although they are most useful on flat or slightly curved surfaces. These are commercially available or you can make your own (a much more economical tool).

Emery and polishing papers

To make sanding sticks a la Alan Revere

You will need flat paint stirring sticks or the equivalent wooden slat about 1” wide by 1/8”-3/16” thick (one stick each for each grit of emery paper you want to use).

- Place a sheet of emery paper under the stick, lined up with the edge of the stick.

- Use a scribe or a steel burnisher, a ballpoint pen, or the smooth edge of a butter knife to crease the paper along the other edge of the stick.

- Roll the stick on the paper until you can crease it at the next edge of the stick.

- Keep on rolling the stick and creasing the paper until the whole sheet of emery paper has been rolled on the stick.

- Staple the edge of the paper three times along the edge of the stick to hold the paper in place.

- Tear off worn out paper as it is used, uncovering the next fresh layer.

Very-Cool-Tools Alert

A Scotch Stone (also called Water of Ayr Stone or Tam-o-Shanter Stone) is a natural stone that has historically been used to eliminate fine scratches on metal. It can be shaped by filing, sanding, or grinding to fit into restricted spaces. Use under flowing water or in a pan of water. Rub this tool along the scratches.

In his book, Bench Tips for Jewelry Making, Bradford M. Smith mentions a great little tool for hand sanding in tight spaces. It’s the PrepPen Adjustable Sanding Pen, and it uses glass fiber to remove scratches. Keep it wet and scrub on the scratches. It’s available all over the Internet.

PrepPen

Machine sanding unwanted scratches: on untextured surfaces

The following tools can be used to remove shallow scratches on untextured metal surfaces:

- Slotted mandrels used with strips of emery paper or Tr-M-Ite paper, in a range of grits

- Sanding drum mandrels (also called drum arbor mandrels) with abrasive paper strips

- Snap-on mandrels and abrasive paper discs

If the scratches are very deep, you may need to begin by removing materials more aggressively. You can use a steel burnisher for this, after which you can proceed with emery or other papers as above. Slide the burnisher along the line of the scratch, not across it.

Use AdvantEdge Silicone Polishers, Cratex Wheels or similar polishing wheels for flex shafts/rotary tools. These come as coarse to very fine abrasiveness, are color-coded and come in a range of sizes and shapes: wheel; point; knife-edge; bullet; cylinder; inside-ring; pin. They are usually mounted on a screw mandrel. These types of wheels can be custom-shaped for specific tasks by running them on a commercially available shaping block; a very rough stone; cinder block material; or on a diamond file.

Note on abrasive wheels for flex shafts

Abrasive wheels are available permanently mounted on a mandrel, but I have found these to be impractical. Once the wheel is worn down, the mandrel is useless and must be discarded. With screw mandrels, when each accessory is worn down, the remnant of the wheel is discarded, but the mandrel can be re-used with a new wheel.

When using these wheels, a gentle touch is necessary, especially with sintered metal, because of the lower density of the metal. They will cut metal very fast. You can accomplish a lot with a little bit of effort.

Machine sanding unwanted scratches: on textured surfaces

For textured and/or untextured surfaces, use 3M Radial Bristle Discs, progressing from coarse to fine (Brown or White to Blue).

Sanding hard-to-reach openings

Sometimes there’s a spot that needs special attention but is very hard to reach using any of the above methods, sort of like an itch on your back that you can’t quite reach.

The old packing tape/emery paper combo

- Use clear packing tape to cover the back of one sheet each of 220, 440, and 600 grit emery paper.

- Mark grits along the backs of each sheet with a permanent marker.

- Cut narrow strips of the taped emery papers to create narrow sanding strips that you can slip and slide into any narrow openings on your piece.

What’s the next step?

“Metal is polished when you create smaller and smaller scratches until they are invisible” Alan Revere “101 Bench Tips for Jewelers”

How to do this?

- Sand

- Buff

- Polish

Surface finishing terminology; buffing and polishing, and finishing, Oh My!

So now you’ve eliminated the flaws on the surface of your piece. Check it out carefully with a magnifier, like an Optivisor, to make sure the surface looks the way you want it to look. If you want you can stop here. If you want a brighter finish, you can go on to the final finishing steps.

Let’s talk a little about those terms “Polishing”, “Buffing” and “Finishing”. And what I really want to say is that the terms have become almost interchangeable in common use (though they’re really not) and, because of that, it can seem confusing.

I think of finishing as preparing work for the final polishing and buffing. It is generally considered to be that step between sanding and polishing. Buffing uses buffs and/or wheels. But since polishing also can require using buffs and compounds, polishing is also really a form of buffing. Are you confused yet?

“Think of a buffing wheel as sandpaper that you keep renewing”, Tim McCreight “Jewelry; Fundamentals of Metalsmithing”

and

“Buffing is a mildly abrasive process, whereby a charged rotating wheel is brought into contact with the work…Polishing is the final finishing stage in which a high luster is imparted to metal using rouge-charged rotating wheels or brushes. Metal surfaces may also be polished by burnishing and with polishing papers”

Alan Revere “Professional Jewelry Making; A Contemporary Guide to Traditional Jewelry Techniques”

HOPE THAT HELPED!!!!

Polishing depends on a combination of:

- the buildup of heat, by friction against the metal object

- the correct abrasive compound

- a firm, not hard, pressure of the buff on the metal surface

This combination, when balanced, will cause the surface of the work to ‘flow’, producing a bright, smooth surface.

Follow the yellow (red, white, green, black, and brown) brick road; I’m talkin’ about polishing compounds

Me and abrasive compounds

Let me say that I almost never use any polishing compounds! If I have used any, it has been on a piece that, unlike most of my work, required a very highly polished surface. I also have used only one compound, and it was one that was designed for ferrous and/or nonferrous metals and which cuts very fast. I’m not fussy, I just want to get where I want to go, and fast.

These pesky abrasives are called “polishing” compounds, but they are really buffing AND polishing compounds, because they are mostly used on buffs of one kind or another. That being said, and making things more complicated, there are a lot of buffing/polishing compounds available:

- Tripoli

- Bobbing White Diamond

- Crocus cloths

- Jeweler’s Rouge (up to five different formulas)

- and others

They are traditionally used in the following order:

- For Buffing: Tripoli or Bobbing

- For Polishing: White Diamond and the Rouges

They are usually metal-specific, though many can be used on several different metals. These are all abrasives embedded in a binder and, except for Crocus Cloths, formed into rectangular bricks or blocks. These binders are grease or wax based, which makes using them messy and can make them difficult to clean up after using them.

The new kids on the block

There are some newer compounds whose abrasives are embedded in a water-soluble binder. The abrasives remain just about the same, but clean-up is much easier. All of these compounds work very fast and, if used according to the manufacturer’s instructions, can produce a clean to very highly polished surface. When these compounds are used a clean-up of some kind is always needed (This is not my idea of fun!).

Safety Note on Polishing Compounds

These compounds create a lot of dust. Your eyes and your lungs must be protected when using these compounds. This means using safety glasses or a face shield, and active ventilation to remove the dust.

When using a rotary tool or polishing wheel of any kind to buff or polish, do NOT wear gloves for any reason, because gloves can get caught in the rotation of the tool. Not a pretty sight!

A little more info on those buffing/polishing compounds

Polishing compounds are formed into bricks to be used by hand or by machine buffing on a rotary tool. The manufacturers of compounds almost always describe the metal(s) on which to use each compound and for which resulting finish. You can generally find these descriptions in your supplier’s catalogue. Compound is applied to assorted accessories (buffs, wheels, brushes). This is called ‘charging’. The accessory is then rubbed on the metal surface by hand or by machine.

Hand buffing/polishing

Commercially available polishing sticks

Polishing sticks can be purchased ready-made with sanding abrasive material already attached. They are available in the following cross-sections: flat, round, triangular, half-round and tapered. The abrasives wear out eventually and the sticks can then be used with whichever compound-charged cloth you may want to use. (The process of impregnating anything with a compound is called ‘charging’… more about that later).

Making your own polishing sticks

- Trim a piece of leather or thick felt to fit the flat surface of a flat stick (like a paint stirrer) or to a piece of wood in the shape you need.

- Epoxy the material to the stick.

- While the glue is drying, place a heavy book on top of the flat stick to keep the material flat.

- Make multiples of these polishing sticks, the quantity depending on the number of different polishing compounds you want to use (and also on the variety of metals you are using them on).

- Charge each stick by rubbing the compound on the material on the stick.

Simple hand buffing/polishing

Charge or apply some compound to a 100% cotton cloth and rub the metal with the cloth. I like old cotton dress gloves for this, but cotton flannel or clean T-shirts work well, too.

Buffing in tight spaces

Charge the tip of a toothpick with a little buffing compound and rub the charged tip on the metal.

Machine buffing/polishing

What about those buffs?

With a rotary tool, all the compounds must be applied to accessories (buff, wheels and brushes).

Fiber buffs, brushes, and wheels are available in the following materials:

- muslin (stitched or unstitched)

- felt (hard, soft)

- flannel

- chamois

- metal brushes

- natural bristle brushes

- and other materials

Buffs come in the following shapes:

Wheel, goblet, pointed cone, round cone, cylinder, knife edge.

The above accessories can be screwed to a mandrel or be purchased permanently mounted to mandrels. (As I mentioned earlier, the accessories that are permanently mounted are not as economical to use)

Charging the buffs

The application of compounds to buffs, brushes, and wheels, is called “charging”.

Charging is done by:

- inserting the accessory’s mandrel in a flex shaft or other rotary tool.

- rotating the accessory against the polishing compound brick until a small amount of compound has transferred to the accessory.

Fluff and stuff

On some muslin buffs, loose threads fly off into the air or extend out from the buffs as you charge them with compounds. (A really good reason to wear a face shield). For those threads that are still hanging off the buff, use a pair of scissors to trim them. Loosely stitched buffs can be trimmed by mounting them in a rotary tool and spinning them against the edge of an old coarse file.

How to use compound-charged buffs, wheels, brushes, etc.

Each compound must have a dedicated buff (or cloth), and each charged buff must be used with only one kind of metal.

For example, even if you like the look of a finished produced on both bronze and silver using Red Rouge, you must charge and use different buffs for each of those metals. If you use several different compounds in the process of polishing a particular object, you must remove the first compound from your metal, by de-greasing or washing (see below), before using the next compound, to prevent contaminating the next compound+buff you will use and messing up your metal surface.

These compounds work very fast, that is, they cut a lot of metal in a very short period of time, so must be used with a gentle touch on sintered metals. You don’t want to lose any of your precious textures or dig into the surface of your piece. Practice on a scrap piece might help you get used to using the compounds.

A thrum, a toothpick and a cotton swap go into a tricky spot

Suppose you have a metal object with lots of small openings, like filigree or pierced work. You might need to get into the edges of those open spaces to clean them up. A traditional method for doing this is called Thrumming. A piece of thread or string is secured to your benchtop (held in your vise or threaded through an eyehook) then threaded through one of the open spaces and held taut in one hand. Charge the thread with a buffing or polishing compound, by rubbing the compound along the thread. The piece is then slid back and forth along the thread.

And here comes that neat little toothpick again…

- Break it in half.

- Mount it right in your rotary tool.

- Charge it.

- Run the rotary tool slowly, and away you go!

The cotton swab joins the party!

- Break a cotton swab in half.

- Chuck it in your rotary tool.

- Trim it or shape it if you want (Run it against coarse sandpaper).

- Spin it against a compound to charge it.

A little side note on what I like my metal to look like

I like my pieces to have a soft, not too bright finish. For me this means that I normally don’t use any polishing compounds… almost never even take them out even to look at them! I’ve had the same bar of compound, White Rouge for way over ten years. (The rest of story later.)

What I want to say is that you can always choose what you want your piece to look like and the choices are broad:

highly polished; lightly polished; scratch-finished; patinated; unpolished. The end result only has to please you… there is no right or wrong end result.

Removing compounds from your piece

When you’re finished using the final polishing compound and have achieved the surface you like, really work on de-greasing your metal. If you used any of the compounds with water-based binders, this will be much easier to do. A good washing in a gentle dishwashing liquid or an agent like Rio’s Sunsheen, wearing gloves, should remove all grease. Household ammonia or Citrasolv also work very well but should be ventilated.

As long as there are no stones set in your piece, if you have an ultrasonic cleaner, put some dishwashing liquid and water in it and use it to degrease your piece. Even your fingers can leave grease on your piece, especially If your piece has a highly polished surface. After you degrease and rinse it, dry your piece with a lint free paper towel or in sawdust to prevent re-depositing grease, spotting it, or scratching it.

Mass finishing

What is this really?

Mass finishing is a process generally used for surface finishing single to multiple metal pieces of jewelry or other small metal objects. It is accomplished by using mechanical equipment that is randomly called finishers, polishers or tumblers.

Yup… this is just to confuse you. Really!

There are three common types:

- Rotary Tumblers,

- Magnetic Finishers

- Vibratory Tumblers/Finishers

There are also Ultrasonic Finishers available. These is not the same machine as Ultrasonic Cleaners.

All of them, other than the ultrasonic finishers, work by continuous movement of the jewelry in containers or barrels, in which there is a medium (steel shot, plastic, hardwood, shell, or ceramic media), either dry, or in water plus lubricant or a compound. They do not produce a work-hardened piece of metal. Only the surface of the metal is hardened, like a shell, by the compressive action of the tumbling medium against the jewelry pieces. They generally require a lubricant of which there is a range of lubricants, sometimes called compounds, available.

The types of finishers, polishers, and tumblers

Rotary tumblers:

- contain rotating roller tracks supporting a barrel or container

- use carbon steel, stainless steel, and other media as burnishers (sometimes called ‘shot’)

- require water and a lubricant (there are a range of lubricants or compounds available)

- are slower to complete the process than magnetic finishers and some vibratory finishers

- are the least expensive to purchase of all the finishers

- may also be used to tumble river stones and some glass, using the appropriate medium.

Loading rotary tumblers

- Mix water and lubricant according to manufacturer’s specifications.

- Add steel shot or porcelain to the barrel, according to the manufacturer’s specifications, but no more than 4 parts shot to 1 part jewelry or object, by volume.

- Add lubricant solution to just cover the level of the media/jewelry, no more than ½” above.

- Cover the barrel and set it on the roller tracks of the tumbler machine. Turn on the tumbler.

- Tumble for ½ hour, turn off the machine, open the barrel and check the finish on your pieces.

- If insufficient finishing has occurred, replace the pieces and the lid. Run the machine for another ½ hour, check again.

- Repeat until you are satisfied with the finish.

A note on lubricants

If you don’t use enough lubricant, the steel shot can transfer to the surface of the pieces being tumbled, giving a more grey and less appealing color to your metal.

Rotary Tumbler

Magnetic finishers

- contain strong rotating magnets beneath the container

- use very small, magnetized stainless steel pins and/or balls (sometimes called ‘shot’)

- require water and a lubricant (there are a range of lubricants or compounds available)

- very quick and quiet finishing process

- range of prices and sizes available

- produce a bright, burnished surface on metal

- smaller machines have less powerful magnets, requiring much smaller loads of metal objects.

Magnetic Tumbler

Vibratory finishers

- have vibrating bases and containers in a range of sizes

- use ceramic, hardwood, plastic, steel, or shell media (whatever is specified by the manufacturer)

- may be used dry or with water and a lubricant or compound, whatever is required by the specific media

- some can be used for polishing glass and ceramic objects, as well as metal

- some require a flow-through system for wet finishing

- are available in a very wide range of sizes and cost

- can produce excellent finishes

- the largest are the most powerful of all mass finishers

- most expensive to purchase of all mass finishing equipment.

What I like

I want my pieces to have a sense of History, to feel as if they’ve been around for a while. So of course, this means, I probably don’t want a very highly polished piece. I like texture and I want the texture to POP! So, of course, I patinate (more about that later).

How I get what I like

If my pieces have been fired in carbon, alumina hydrate, or vermiculite, I rinse them off until none of the residue of those materials remains. Next, I usually run the pieces through my magnetic finisher with:

- a handful of stainless steel finishing pins

- about a tablespoon of burnishing compound (I use Rio Sunsheen)

- for about 15 minutes.

My magnetic finisher is #202-201 in the Rio Tools & Equipment Catalogue (just so ya know). I might brush the pieces first with a brass brush and lubricant, then run them through the magnetic finisher. Sometimes I’ll do this just to get an idea of what the surface really looks like. I could, instead, mount 1” squares of Scotchbrite on a screw mandrel and use the flex shaft to clean and smooth the metal oxides on the surface of my metal clay objects. This does compress the surface of the metal slightly, but I generally prefer the slightly stronger compression of the steel shot in the finisher.

Why use the magnetic finisher right out of the kiln?

When the pieces come out of the finisher, any the flaws will show up and I can see them more easily and therefore clean them all up before going on with the finishing process.

One more time… a note about the terminology

Although the lubricants are called burnishing compounds, that’s actually inaccurate terminology. The steel pins actually do the burnishing. The compound lubricates the pins allowing them to slip and slide around the metal objects, without pinging, marking them, or depositing any of the steel onto the surface of the silver.

Ariamuara

What are radial bristle discs and why I love them

RBD’s are synthetic brushes embedded with abrasive. No polishing compound is needed, and therefore, no aggressive cleanup is needed. RBD’s create relatively little heat. They are available in a range of grits from very coarse to extremely fine. They can easily produce a finish from brushed to very bright.

How to use radial bristle discs

RBD’s must be used on screw mandrels in a rotary tool that can be run at 10,000 rpm. Three to six discs should be mounted on the mandrel at one time. The discs must be mounted so that their bristles rotate in the direction the rotary tool revolves, not against the rotation. If they’re not mounted facing the right way, the bristles will bend and tear off, destroying the discs.

The discs should be rotating at high speed, gently touching the bristles to the surface of the metal. Do not press them hard against the metal, as this accomplishes nothing more than bending and compressing the bristles.

You don’t have to clean off the piece between grits of the discs. There’s nothing deposited on the metal, so there’s no heavy-duty de-greasing (just your skin oil). This can make for a very happy jeweler.

I use a flexible shaft. It’s the most important tool in my studio. As a matter of fact, I have five of them, with different ‘accessories’ mounted in them, so I don’t have to change out tools all the time.

Radial bristle brushes

A note about my flex shafts

I use a basic flex shaft set-up, with a simple handpiece, like the Foredom #30 for most operations. I prefer this to the quick-change handpieces that are available. Those handpieces only have one size openings in their chucks. I need infinite chuck openings, because I have mandrels of various diameters. I use the Lucas rheostat (foot pedal), because it really allows for accurate speed control. I dedicate one flex shaft to a hammer handpiece, which I use for texture and stone setting. I dedicate another to a Kate Wolf belt sander. The other three are dedicated to grinding, polishing, drilling, texturing, sanding, etc.

If I want, I can add different textures to the surface of my piece at this point. For example, I can engrave, stamp, burnish, etc. Now’s a good time to do this. Then I might toss my piece back into a magnetic finisher. I run the finisher for about 10-15 minutes.

Where do we go from here?

I have some choices to make, which may vary with the specific piece on which I’m working:

- Stop here and do no more

- Patinate

- Enamel, then patinate

Whatever I decide to do, I have to degrease the metal. For patinating, I will simply rinse the piece. For enameling fine silver (which is what I usually use), wearing gloves, I would rinse and brush with a fiberglass brush under water. I’m not going to talk more about enameling, because that’s a whole other subject. After the piece has been enameled, I would then tumble it again, and if, patinating it, I would go on to do that.

Patination

There are many chemicals for adding patinas to metal surfaces. For example:

- Rio Grande offers at least seven options, in many different forms

- Otto Frei, thirteen

- Gesswein, five

- Contenti, three

- Metalliferrous, seven

Since I primarily use fine silver and sterling silver in my work, I like to use Liver of Sulfur as my preferred patination chemical.

When I use bronze metal clay (I like FastFire BronzClay), I fume it:

- coated with table salt

- suspended above a dish of ammonia

- in a sealable plastic container

About Liver of Sulfur

Liver of sulfur (LOS) is relatively innocuous. It does generate fumes, so active ventilation is imperative. Wear rubber, latex, or nitrile gloves when handling it, or use nonreactive tweezers (stainless steel, bamboo, or plastic). LOS smells like rotten eggs, and will make your ungloved hands smell like that, too.

LOS is packaged in three different forms: as chunks, as a gel, or in solution. I use the chunks which retain their strength longer than the solution. (I have no experience using the gel.)

How to use Liver of Sulfur chunks

Drop a chunk of LOS into hot water in a small nonreactive (stainless steel or Pyrex) bowl. LOS works best when it’s hot, so you can also use a stainless steel pot and heat it on a hotplate.

SAFETY NOTE: DO NOT BOIL LIVER OF SULFUR AS THIS CREATES VERY BAD FUMES.

It doesn’t need to be boiling, just hot… and ventilate, ventilate, ventilate.

The color of the solution should be a deep yellow, about like the color of an egg yolk. When I’m finished applying this solution, I can store it for several days and re-use it. Drop the degreased metal object in the hot LOS solution. Remove the object after a few seconds, either with gloved hands or tweezers. Rinse the piece in hot running water and re-immerse it in the solution. Repeat this procedure until the patina pleases you. Rinse the piece in hot water with a little dishwashing liquid. You may also rinse with a few drops of soapy household ammonia in hot water, as this helps to neutralize the liver of sulfur.

OK, so you don’t happen to have liver of sulfur on your shelf.

If you don’t have any LOS and you need to patina a piece, you can use hard-boiled egg yolk. That rotten egg smell is sulfur.

- Boil one or two eggs

- Peel eggs and break open so that the yolk is visible.

- Place the eggs and metal object in a jar with a screw lid and screw on the lid.

- ….wait….wait… until the metal is dark enough to suit your taste. This may take a few days, depending on the age of the eggs…older = better.

My final finishing steps

I have used several different procedures to finish my work after patination and rinsing. My decision will always be based on the piece on which I’m working.

If I want an all over patina on the surface of the object, I have two choices:

Choice #1: Brush with a jeweler’s brass brush and liquid dishwashing detergent

Choice #2: Use the very finest grit of Radial Bristle Disc, the pale green, to very lightly remove some of the patination from the metal.

If I want to more carefully remove the patina only from the high spots of a textured surface, I also have several choices:

Choice #1:

- Put on an old, clean, white, 100% cotton dress glove or wrap a 100% cotton soft rag around your index finger

- Dip your index finger in a little olive or canola oil

- Dip that same finger in a very little bit of fine powdered pumice

- Wear a particulate mask to use this

- Gently wipe your finger across the metal surface, removing the patina from the high spots, leaving the recessed areas darkened

- Rinse the metal under hot water, using dishwashing liquid to remove all traces of the oil and pumice.

Choice #2:

Again, use the very finest grit of Radial Bristle Disc, the pale green, and with a very light touch, remove some of the patination from the high spots on the metal. I then might rub down the entire piece using a Sunshine Cloth and rinse it again with hot water and liquid dishwashing detergent. I don’t generally fire stones in metal clay, so now is the time when I would begin to set stones in the piece, either as bezels integrated in the metal clay prior to firing or by soldering bezels to the piece before tumbling and patinating. After setting stones, I check for any marks I might have made, correct them and I’m done!

A brief bibliography of some books with the scoop on finishing

101 Bench Tips for Jewelers; Alan Revere

Bench Tips for Jewelry Making; Bradford M. Smith

The Complete Book of Jewelry Making; Carles Codina

The Design and Creation of Jewelry, Robert von Neumann

The Flexible Shaft Machine, Jewelry Techniques; Harold O’Connor

Jewelry, Contemporary Design and Technique; Chuck Evans

Jewelry, Fundamentals of Metalsmithing; Tim McCreight

Making the Most of Your Flexshaft; Karen Christians

Professional Jewelry Making, A Contemporary Guide to Traditional Jewelry Techniques; Alan Revere

Secret Shop Weapons; Ann Cahoon and Chris Ploof

Tumble Finishing for Handmade Jewelry; Mass Finishing on a Small Scale; Judy Hoch

Some suppliers

Almost all of the suppliers listed below carry everything mentioned above, including flex shafts, magnifiers, tumblers and magnetic finishers, polishing compounds, burnishers, polishing, papers, kilns. If you search a site that doesn’t stock a specific object, try another supplier.

Amazon: amazon.com

Contenti: contenti.com

Gesswein: gesswein.com

Harbor Freight: harborfreight.com great low price rotary tumblers

Metalliferrous: store.metalliferous.com

Otto Frei: ottofrei.com

Rio Grande: riogrande.com

Contact Information for Linda Kaye-Moses

Address: Post Office Box 1758, Pittsfield, MA 01202-1758 e-mail: lindakm@berkshire.net

Please feel free to contact me if you have any questions about finishing

copyright 2022 Linda Kaye-Moses

All rights reserved. No part of this document may be reproduced or used in any form or by any means graphic, electronic, or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, taping or information on storage and retrieval systems without the written permission of the author, who is the owner of this copyright. The Author gives permission to AMCAW and its members to download the material contained in this document. Due to differing conditions, materials and skill levels, the author and AMCAW disclaim any liability for unsatisfactory results or injury due to improper use of tools, materials, and/or misuse of the information contained in this document.