For many of us, our first foray into jewelry design fell under one of several categories:

- beading,

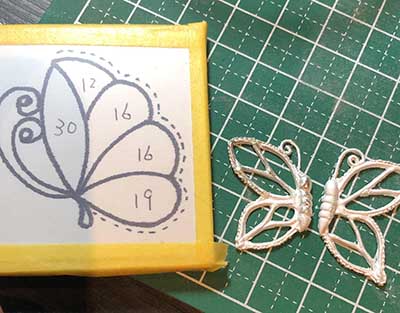

- wirework,

- metalsmithing,

- or maybe even metal clay.

Wirework has the unique ability to capture, combine, and connect all these design methods, greatly expanding your jewelry design options.

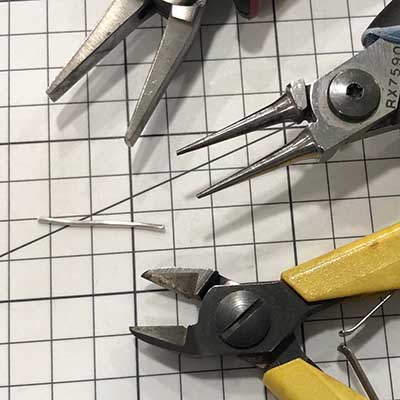

All kinds of wire will be covered in this article including fine silver round wire and bezel wire, Sterling silver wire, Argentium wire, copper wire, Sterling silver headpins, Sterling silver rivets, flex wire and more.

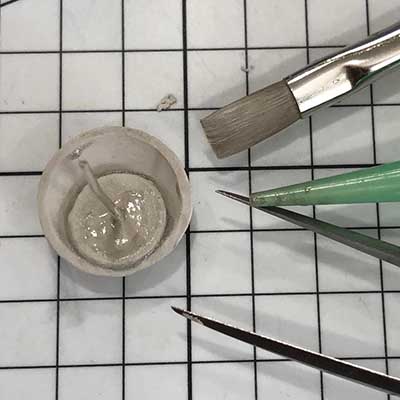

This article gives an overview of several techniques for incorporating wire into metal clay pieces, breaking the categories into options for adding wire pre-firing, mid-firing, and post-firing. There are many additional resources in the AMCAW Learning Center and the member only tutorials that will help you find out more detailed information for many of the techniques referenced here.

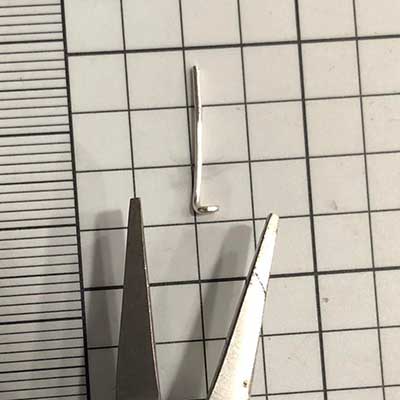

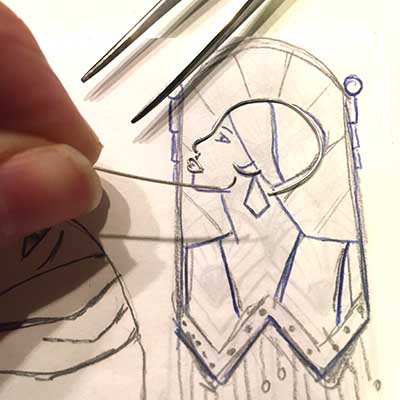

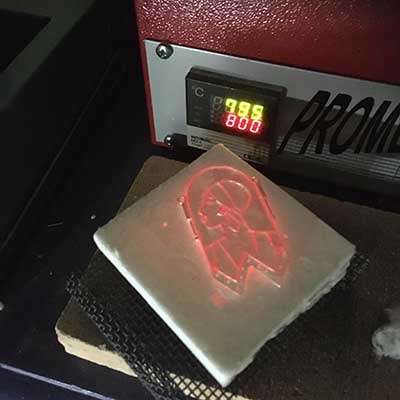

There are some important guidelines to follow when you are considering adding wire into your unfired silver metal clay piece. One is absolutely key when you are working with silver clay as it informs your design process even before you put pencil to paper. It is tempting to think that incorporating sterling silver wire will strengthen your piece and this is true, but only to a point. It is possible to safely add sterling wire to silver clay up to 1300°F/705°C if you plan to fire for less than an hour.

However, under the high-temperature/long-hold kiln-firing conditions common for many silver clays, sterling silver wire undergoes a structural change. It begins to melt from the inside out. Although the wire may look strong after firing, it has degraded internally, becoming very brittle, and can easily break when any twisting, bending, or shaping force is applied. This problem is solved by substituting fine silver wire and elements in place of sterling. Embedding Metal In Metal Clay is an excellent article in AMCAW’s Learning Center Resources that addresses this topic in more depth.

Adding sterling wire or other elements post-firing is an excellent option. You can solder, wire-wrap, or twist away to your heart’s content and embellish your pieces with colored beads and even colored craft wire.